President #31, C-SPAN Historians ranking #34

The Pac-10 goes to the White House and is not Invited Back

Herbert Hoover seemingly had everything you would want from a President. He was well-educated, with a degree in geology from Stanford. He had traveled the world. He was a successful businessman. He showed he could organize people all over the world to ward off famine.

And when he became President, he was awful. Faced with an unprecedented economic crisis (that was not his fault), Hoover, in crude test pilot/astronaut speech, screwed the pooch. Whatever Hoover had accomplished before in life, was forgotten under the weight of massive unemployment and a shrinking economy,

William E. Leuchtenburg, who has written extensively on the history of the Great Depression, does not paint a sympathetic portrait of Hoover. Instead, Hoover comes across as vainglorious, although tempered by a desire to serve the public. But, Hoover wanted the public to respect him and love him because he was Herbert Hoover. Out of office, Hoover turned into a bitter reactionary. But, as Hoover would say in his retirement (he lived until he was 90) about how endured all the taunts, “I just outlived all the bastards.”

Herbert Clark Hoover was born into a Quaker family on August 10, 1874 in West Branch, Iowa. He was orphaned at the age of 10 and sent off to live with an uncle in Oregon. Not surprisingly, Hoover had a very unhappy childhood. His uncle, who had recently lost his son, didn’t find Herbert Hoover a suitable replacement. But, Hoover did get an education. And, in 1891, Hoover was admitted to the first ever class of a new university in California: Leland Stanford Junior University. Hoover’s field of study was geology.

While at Stanford, Hoover found the eye of another woman who was in the geology major. Actually, she was the ONLY woman in the geology major at the time. Her name was Lou (short for Louise) Henry. The two would eventually marry in 1899. In addition to raising two children, Herbert and Lou collaborated on an English translation of the 16th Century textbook on metallurgy called De re metallica.

Hoover was also the student manager of the football team. He is credited with coming up with the idea for the first Cal-Stanford Big Game in March of 1892. Stanford won the first meeting 14-10, although the game was delayed supposedly because Hoover neglected to bring a football with him.

Fresh out of college, Hoover managed to get a job with the English mining firm of Bewick, Moening, and Company. He traveled the world inspecting mines for the company. He became an expert at getting mines that were not meeting production quotas up to speed. By the age of 27, Hoover was a full partner in the firm and moved to London fulltime.

In 1908, Hoover left Bewick and became a consultant. He made millions hopping around the globe trying to get mines to produce more. His style was autocratic, but highly successful.

Leuchtenburg points out that despite Hoover being orphaned at a young age, he didn’t try to be much of a parent to his own two sons. While on his frequent travels, he would communicate infrequently with his children and even his wife.

When World War I began in 1914, Hoover’s public profile shot up. Hoover helped finance the journeys of numerous American expatriates back to the United States. Many had found their lines of credit cut off by banks because of the war. But, the biggest problem Europe faced was hunger.

Belgium was the country where much of the initial fighting took place, and, according, it suffered the most. Hoover managed to convince both the British and German to allow him to bring in relief supplies to prevent a humanitarian crisis. Hoover was also determined to make sure that the relief went directly to the people who needed it, and was not siphoned off to any army. Hoover’s efforts in Belgium made him a worldwide figure.

Once the United States entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson summoned Hoover back to the United States to head up the newly created Food Administration. Hoover was charged with keeping America’s food supply going to meet the added demand of a war.

Hoover did not want to have to resort to rationing. Instead, he created a small army of volunteers (nearly all of the women) to go door to door to encourage people to forego meat on Mondays or wheat products on Wednesdays. Hoover was given wide latitude by Congress and the President to act as he saw fit. He was dubbed “the food czar.” No matter what the title was, Hoover got results. The United States did not have to force the rationing of food during World War I.

When the war was over, Hoover was possibly the most popular political figure in the United States. Hoover supported Wilson’s efforts during the negotiations at Versailles. He came out in favor of the League of Nations. He opposed the stepped up prosecutions of Communists by Wilson’s Attorney General Mitchell Palmer. Hoover was the darling of the Progressive movement. One prominent Democrat, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, hoped that the party could convince Hoover to run for President in 1920.

There was one problem: nobody knew what party Hoover belonged to. Hoover had never explicitly said so. Finally, in the summer of 1920, Hoover announced that he was a Republican. One reason for this was that Hoover did not wish to be identified with racist Southern Democrats. Also, Hoover could see that the Democrats were sure losers in 1920.

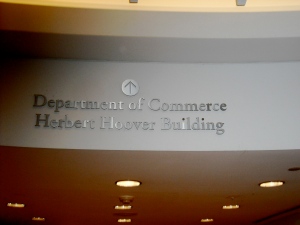

After Warren Harding swept into office in the 1920 election, Hoover was offered his choice of Cabinet positions. Hoover opted for the job of Secretary of Commerce. This was an unusual choice as the job had little cachet attached to it. (Can you name the current Secretary of Commerce?)

Hoover revolutionized the office of Secretary of Commerce. He was able to convince the President and Congress to add more responsibilities to the job. Under Hoover, the Commerce Department took control of the Census, the regulation of air travel, and the regulation of radio frequencies. Hoover established commissions to study pretty much any issue that he felt that the Commerce Department might have some responsibility for.

Hoover revolutionized the office of Secretary of Commerce. He was able to convince the President and Congress to add more responsibilities to the job. Under Hoover, the Commerce Department took control of the Census, the regulation of air travel, and the regulation of radio frequencies. Hoover established commissions to study pretty much any issue that he felt that the Commerce Department might have some responsibility for.

After Calvin Coolidge became President after the death of Harding, Hoover remained in the job. Coolidge did not particularly care for Hoover, sarcastically referring to him as “the Boy Wonder.” But, Hoover could not be replaced. He had made himself indispensible in the eyes of the public.

During the great famine of 1921 in the Soviet Union, Hoover led a relief effort there, despite the objections of many who wanted nothing to do with the Communist regime there. Ironically, Hoover may have done more harm than good. Soviet foreign policy expert George Kennan would later claim that Hoover’s efforts in the USSR served only to legitimize the leadership of Lenin. Hoover would be one of the few Republicans who wanted to normalize relations with the USSR. (This wouldn’t happen until 1933.)

In 1927, one of the largest natural disasters ever to befall the United States hit. It was the Mississippi River Flood. Over 700,000 people had to leave their homes. 27,000 square miles of land were flooded. Over 200 people died.

Hoover was tabbed by Coolidge to head up the relief efforts. This was an area where Hoover did his best. He traveled throughout the affected areas, ordering people to fix problems, not in a week, not in a day, but NOW. Orders were given by Hoover. He expected them to be obeyed. Hoover also made sure that aid was equally distributed to both white and black victims of the flood. This earned him the enmity of some in the South, but further burnished his image with Progressives.

When Calvin Coolidge chose not to run for another term in 1928, Hoover was the presumptive Republican nominee for President. He faced little opposition and had to do little campaigning to win the nomination. Although the Republican Convention was held in Kansas City, it was still not the practice at the time for the candidate to be present to receive the nomination. So, Hoover gave his acceptance speech at Stanford Stadium.

The election of 1928 was no contest. The Democrats nominated New York governor Al Smith, who was the first Catholic nominee from a major party. America was not ready to elect a Catholic, especially one who favored the repeal of Prohibition. Hoover won 58% of the popular vote and 40 of the 48 states. Hoover even won four states of the Confederacy, Texas, Florida, Virginia, and Tennessee, which was quite a feat for that era.

Hoover’s inaugural address was full of high-flying language.

We are steadily building a new race—a new civilization great in its own attainments. The influence and high purposes of our Nation are respected among the peoples of the world. We aspire to distinction in the world, but to a distinction based upon confidence in our sense of justice as well as our accomplishments within our own borders and in our own lives.

—-

This is not the time and place for extended discussion. The questions before our country are problems of progress to higher standards; they are not the problems of degeneration. They demand thought and they serve to quicken the conscience and enlist our sense of responsibility for their settlement. And that responsibility rests upon you, my countrymen, as much as upon those of us who have been selected for office.

Ours is a land rich in resources; stimulating in its glorious beauty; filled with millions of happy homes; blessed with comfort and opportunity. In no nation are the institutions of progress more advanced. In no nation are the fruits of accomplishment more secure. In no nation is the government more worthy of respect. No country is more loved by its people. I have an abiding faith in their capacity, integrity and high purpose. I have no fears for the future of our country. It is bright with hope.

Hoover had big plans for his Administration. He wanted to streamline government regulations and was prepared to establish numerous commissions to accomplish this. (This has been a popular technique since). There was a proposal to build what would become the St. Lawrence Seaway, the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, a dam in Boulder Canyon of the Colorado River (which would become Hoover Dam). There were also plans to reform the Federal prison system. Hoover also canceled all leases for oil drilling on Federal lands.

On October 14, 1929, Hoover attended Game 5 of the 1929 World Series at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. He received a huge ovation from the crowd.

Note: Half-assed attempts at explaining economics follow. Any resemblance between my writing and actual economic theory is entirely coincidental.

Ten days later, Black Thursday hit Wall Street. Over 12 million shares (besting the previous high by 4 million) were traded at the New York Stock Exchange on October 24, 1929. The Dow Jones average dropped from 305 to 299. But, Wall Street said that there was little to worry about. On the following Monday, the Dow dropped to 260. And on Tuesday, it was 230. The slide would continue until 1932. The Dow lost 89% compared to its high on September 3, 1929.

The Wall Street Crash was just one symptom of the many problems of the Great Depression. Banks began to rein in credit (or simply just fail) and foreclose on homes and farms. Industries cut back on wages or laid off employees. People saw their life savings disappear.

Hoover, faced with an unprecedented crisis, took steps that most economists believed only exacerbated the problems. One of the biggest blunders was his signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in June of 1930. This bill raised tariffs to unprecedented levels. The result was a sharp decline in imports. Also, other nations passed their own protective tariff measures.

Despite his background in humanitarian causes, Hoover gave the impression that he didn’t care much about the problems that many Americans were facing. Part of this was from the fact that Hoover was now a President. He had to work with Congress and politicians with different agendas. He found himself in a position where he had less authority to get things done. Hoover was also strongly opposed to any Federal government handouts, feeling that they contrary to the spirit of individualism that he was trying to build in the country.

Hoover was also convinced that the biggest problem with the economy was the Federal Government’s budget deficit. Hoover raised income taxes and sharply curtailed Federal spending. The net effect of this was to suck even more money out of the economy. (For a dissenting opinion, you can read this book.)

By October of 1931, when Hoover returned to Shibe Park to see the Philadelphia Athletics play the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, he was booed. Few Presidents had ever received such a public reaction like that at that time. (It’s not unusual now. Here’s the reaction George W. Bush got in 2001. By 2008, the reaction was different. Barack Obama’s reception at the 2009 All-Star Game could be described as “mixed.”) A growing number of homeless people formed communities that were dubbed “Hoovervilles.”

Despite his wide travels in the world, Hoover was not an expert on foreign policy. He hoped to ease tensions between the United States and Latin America, but ended up sending troops using troops to prop up a right wing regime in Nicaragua, setting up the long battle between the Somoza regime and the Sandinistas that would last until the Reagan years. (Hoover would withdraw the troops before he left office.) Hoover, like most other world leaders of the time, did not do much of anything to stem the rise of German fascism or Japanese militarism.

The nadir of his unpopularity may have been in July of 1932 when a group of World War I veterans marched to Washington asking Congress to pay them a promised bonus for their military service a few years early. The ragtag group camped out in Washington, but Hoover ordered the Army to clear them out. Under the direction of Douglas MacArthur, the Army routed the so called “Bonus Army” from their encampment. The Army was portrayed as using brutal means to accomplish this, although most accounts agree that it didn’t take much force to get the protesters to move. Also, rolling tanks down the streets of Washington tend to make people less inclined to protest.

There was one forward looking project that Hoover tried in an effort to provide some help. In the summer of 1932, Hoover started a program called the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. It was a government entity that would provide loans to state and local government, along with banks and other financial institutions. But, the program was bogged down in bureaucracy and little of the money that the RFC was authorized to lend was spent during Hoover’s term in office.

Hoover was pleased that the Democrats nominated Franklin Roosevelt for President in 1932, feeling that he had a much better chance of beating him in November. Hoover thought that Roosevelt was an intellectual lightweight. But, Hoover could not overcome his unpopularity. He was also no match for Roosevelt as a campaigner. Roosevelt seemed energetic and positive. Hoover was dour and stuffy.

After winning 40 states in 1928, Hoover would win just six in 1932. Hoover received just 39% of the popular vote and only 59 electoral votes, 36 of them from Pennsylvania. Hoover’s home state of California gave him just 37% of the vote.

During the campaign, Hoover was personally hurt by Roosevelt’s claim that Hoover had encouraged reckless speculation in the stock market. (In fact, Hoover had done the opposite as Secretary of Commerce.) Hoover wanted to have Roosevelt work with him during the transition to calm the financial markets. But, Roosevelt refused and remained silent.

On March 4, 1933, Hoover had to hold in his emotions as Franklin Roosevelt took the oath of office. He felt as if his life’s work had all been for naught.

After remaining quiet for about a year after the election, Hoover began to speak out against Roosevelt. He denounced the New Deal programs as socialistic. (Ironically, one of Hoover’s closest friends overseas was British Prime Minister James Ramsay McDonald, one of the most leftward leaning PMs in history.) He considered Roosevelt to be one of the most dangerous men to ever be President. Roosevelt responded in not so subtle ways. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes had the name of Hoover Dam changed to Boulder Dam (it would be later changed back.)

After Roosevelt’s death, Hoover headed up a commission for President Harry Truman that examined government waste and inefficiency. This job won Hoover some plaudits.

Eventually, Hoover took on the air of a beloved elder statesman. The Republicans held “farewell” celebrations for him at their conventions in 1952, 1956, and 1960. The Senate honored Hoover in 1957 with Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy feting the former President. Hoover was too ill to attend the 1964 convention, although nominee Barry Goldwater offered his respects.

Hoover was working on his own biography of Franklin Roosevelt before his death. It has never been published or even released to scholars for inspection because, according to Leuchtenburg, its tone is so strident that it would tarnish Hoover’s reputation more than Roosevelt’s.

Herbert Hoover died on October 20, 1964 in New York City at the age of 90. He was buried back in his native Iowa alongside his wife Lou, who had died in 1944.

Leuchtenburg has penned an interesting biography of a man who was very hard to know. The private side of Hoover was seldom revealed, even to people in his own family. Leuchtenburg tries to shed light on an almost entirely opaque figure.

Hoover was someone who Americans, at least for a while, admired. But they didn’t seem to actually like him. Hoover didn’t want to be liked. He wanted to get things done, but he never could figure out how to get things done as President. When you become President, you have to know how to work with people, not just order them around. Hoover likely came to the White House expecting to do great things, but the Great Depression ended those hopes.

Would Hoover had fared better during a time of prosperity? We don’t know. But, you can only judge Hoover by what he did with the situation he was given. In a country that was losing hope, Hoover offered almost none.

Please note a correction above marked by strikeout and italic type.

Other stuff: Herbert and Lou Hoover are buried at the Herbert Hoover National Historic Site in West Branch, Iowa. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum is part of that site.

After World War I, Hoover started a research institute at Stanford to study the cause of the war. Since then, the Hoover Institution has become of the one most influential conservative think tanks in the United States, covering all aspects of public policy. Some of its fellows have included Condoleezza Rice, George Shultz, Edwin Meese, Milton Friedman, and Thomas Sowell.

Hoover was the last sitting Cabinet member to be elected President and only the fourth one overall. The other three were James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams, all of whom were Secretaries of State.

The only other candidate from the two major parties who attended a Pac-10 university was Barry Goldwater in 1964. Goldwater attended, but did not graduate from the University of Arizona.

I may be the youngest person alive to have corresponded with Herbert Hoover. At age seven, with the help of my mother, I wrote to Hoover wishing him a happy 90th birthday. He wrote back a note of thanks less than a month before his death.

Did Hoover consider not running for re-election similar to LBJ? Was he really that sure he could beat FDR, or was he lacking in self-awareness?

Hoover wanted to be reelected in 1932 because he believed he was the guy for the job. He also sent out feelers to be nominated in 1936 and 1940, but the rest of the Republican Party didn’t want him. Hoover might actually have fared worse than Alf Landon in 1936.

Also, the Republicans were becoming more isolationist and Hoover wasn’t of that bent.

What a shame he couldn’t work well with others with all the skill sets he had. Thanks for a great bio.

My favorite part of this write-up is how the reference to Stanford University links to the U.C. Berkeley website.

Hoover also helped to create the “other” Hoover Institute, the Food Research Institute at Stanford.

“Despite his wide travels in the world, Hoover was not an expert on foreign policy. He hoped to ease tensions between the United States and Latin America, but ended up sending troops in to prop up a right wing regime in Nicaragua, setting up the long battle between the Somoza regime and the Sandinistas that would last until the Reagan years. ”

You seem to get your facts wrong, Hoover actually PULLED troops from there. He ended America’s interventionism and imperialism in Central America,until it was later revived by the post-war Presidents.

Thank you for the correction. I modified the paragraph to what I believe is more accurate.