Can’t We All Just Get Along?

I had not come across this book when it was published back in 2010, but with the renewed interest in all things Lincoln, I was intrigued about a book about the backroom politics that resulted in Lincoln’s election in 1860. Egerton’s book though is not mostly about Lincoln, who is something of a supporting character, but rather on the important figures of the time, whom history has more or less forgotten in the wake of the 16th President’s accomplishments.

The most important character in the book is Lincoln’s Illinois rival, Stephen Douglas. Coming into the election of 1860, Douglas was the most famous political figure in America. He possibly may have also been the most loved and most hated at the same time. In trying to come up with a solution to the territorial expansion of slavery, Douglas came up with a plan that made things worse, popular sovereignty, which would allow the residents of the territories choose for themselves whether or not to allow slavery. This led to even more strife.

In 1860, there were four major candidates for president and one “third party” candidate who drew significant support. The Democrats ended up having four different conventions in two different cities. Southern extremists, called “Fire Eaters”, had no desire to compromise and hoped that the Democrats would fall apart, ensuring a Republican win that would force Southern states to secede. And that is what happened, as the Democrats nominated two candidates, Douglas, a Northerner who owned slaves in Arkansas (indirectly), and John Breckenridge, a Kentuckian who actually didn’t own any slaves.

The Democrats originally convened in Charleston, but could not agree on a nominee because the party required any nominee to get 2/3 of the votes of the delegates. Eventually, some of the Southern states walked out. Some of them tried to form their own convention in another part of Charleston. That didn’t work, so they gave up and agreed to meet again in Baltimore. Then, they split up again and each group nominated its own ticket. Egerton makes the point that the Democrats could have avoided much of this mess if they had chosen their nominee by majority vote and also apportioned state delegate totals by party strength in the state instead of by electoral votes, which ended up giving a lot of votes at the conventions to Democrats from places like Massachusetts, where they stood almost no chance of winning. (Lincoln would win Massachusetts with over 60% of the vote.)

The Republicans were expected to nominate New York Senator William Seward, but the party believed that he would be considered too radical and would not have carried states like Pennsylvania or Ohio (or even New York), so the party turned to Lincoln, who was a popular, yet lightly-regarded figure at the time.

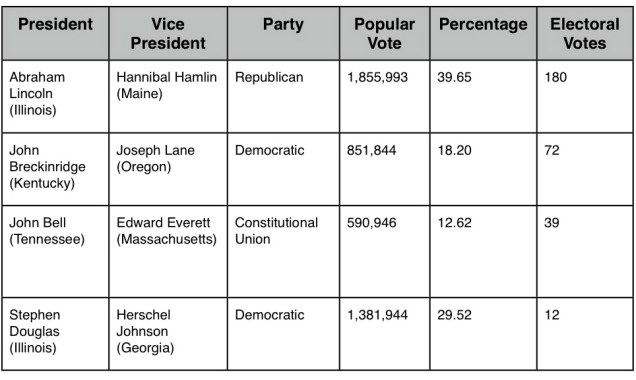

Unusual for the time, the election of 1860 played out the way, political experts of the day thought it would back in June of that year. The Republicans carried all of the Northern states, and only appeared on the ballot in one state that would eventually secede: Virginia. Breckinridge won most of the South. Douglas won only in Missouri and a few electoral votes in New Jersey despite finishing second in the popular vote. Compromise candidate John Bell of Tennessee finished third in the electoral vote despite never espousing any platform. Lincoln won with the lowest popular vote percentage ever, just 39.65%. To a certain extent, Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell all hoped that no one would win a majority of the electoral vote and then force a House vote to decide the Presidency, but they were not very good at math.

After Lincoln’s election, South Carolina and Georgia started the secession movement. There were last ditch efforts at compromise, but the Republicans would not back them, primarily because they granted an expansion of slavery into the territories. Also, Lincoln did not want to come into office with his hands tied to a policy he didn’t support. And so the nation headed off on into the Civil War. The Southern Fire Eaters, whose ideology was based on white supremacy and an antiquated economic system, got their wish of plunging the nation into a bloody conflict. The South thought that the North would cave easily, one in an increasingly great series of miscalculations they would make. The South, while wanting to preserve its “way of life” actually wanted to preserve its economic power, something the North was happy to take from them.

Egerton’s book does a tremendous job of looking at the events of 1860 almost as if you were living at the time. You wouldn’t have thought in 1860 that Abraham Lincoln would become one of the most important historical figures of all time. You would have thought Stephen Douglas was bound for that. But Douglas would die early in 1861, a victim of his own alcoholism. Lincoln’s fame persists. Other figures played their parts in a drama that we hope we never see again.

Odds and ends: At the top of each post, I will put up the results of the election or elections covered in each post. The results will be listed in order of electoral votes received, not popular votes. However, the 1860 election remains the only one to have such an anomalous result. Douglas appeared on the ballot on more states than Lincoln.

Senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama was originally chosen as Douglas’ running mate, but he declined the nomination. Herschel Johnson of Georgia took his place.

Most election data will be taken from Dave Liep’s U.S. Election Atlas, which is a free source of a lot of interesting election data. Please note that the site uses RED on its maps for Democratic wins and BLUE for Republican wins. The colors used by television networks today were chosen arbitrarily.

John Breckinridge was serving as a Senator when the Civil War began. He sided with the Confederacy (despite Kentucky not seceding). He was expelled from the Senate for his actions. He later served in the Confederate government and, after the Civil War ended, fled to Europe to live in exile until an amnesty allowed him to return to Kentucky in 1868.

Interesting review as I’m reading Team of Rivals and just finished the 1860 election about 50 pages ago. (Representing about 4% of the book.) I was surprised by how much Lincoln worked behind the scenes to get the Republican nomination.

BTW, is this the only election in which two major party candidates from the same state faced off?

In 1920, Harding and Cox were both from Ohio. In 1944, Roosevelt and Dewey were both New Yorkers.

I would have guess that Virginia would have been the likeliest state, but then again those early Virginia guys didn’t have much competition.

Also 1904, Roosevelt and Parker were New Yorkers.