The election of 1884 might not seem too different from an election of the late 20th Century or early 21st Century, but it may be the first one that may have its outcome determined by a gaffe. And not even a gaffe spoken by a candidate, but rather by a well-meaning supporter of one of the principals. But, there was a lot more to the 1884 election according to Mark Wahlgren Summers, a University of Kentucky history professor.

The election of 1884 might not seem too different from an election of the late 20th Century or early 21st Century, but it may be the first one that may have its outcome determined by a gaffe. And not even a gaffe spoken by a candidate, but rather by a well-meaning supporter of one of the principals. But, there was a lot more to the 1884 election according to Mark Wahlgren Summers, a University of Kentucky history professor.

In a freewheeling, at times even irreverent, look back at the events shaping the first election of Grover Cleveland, Summers focuses more on the loser, James Blaine. Summers describes a political party system coming apart at the seams.

Republicans could not hold together their disparate parts, with factions favoring Prohibition or political reform often butting heads. The Democrats benefitted from the end of Reconstruction, which let former Confederates retake control of state governments and effectively end voting rights for blacks.

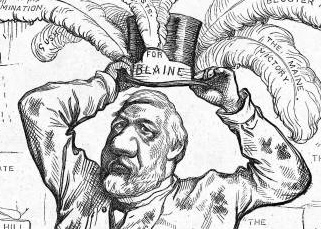

Blaine thought the nomination was his in 1880, but a deadlocked convention turned to dark horse Ohio Representative James Garfield. Garfield was assassinated early in his term and replaced by Chester Arthur, regarded as a political hack by most people, but was surprisingly effective. Arthur wanted to be nominated in his own right in 1884, even though he knew he was dying of kidney disease. The Republicans ended up nominating Blaine in 1884 accompanied by John Logan of Illinois as his running mate.

Blaine, nicknamed “the Plumed Knight”, was considered to be an attractive man who looked like the quintessential statesman. However, Blaine had numerous enemies among the Republicans, including President Arthur, so he was hard-pressed to get all the support and financial backing he needed.

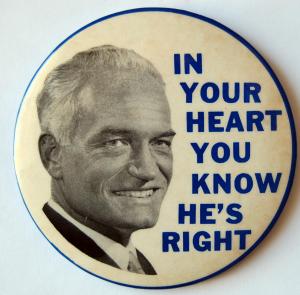

The Democrats nominated New York Governor Grover Cleveland, who had developed a reputation as an honest politician, or as honest as you could expect from a politician in the Gilded Age. The Democrats nominated Thomas Hendricks for Vice President, who was trying to gain the office he nearly won in the controversial election of 1876. (Samuel Tilden, the loser in 1876 was considered the front runner for the nomination despite being extremely ill.)

Early in the campaign, Cleveland was hit hard by accusations that he had fathered an illegitimate child (which most people think he really did), although he took the line that he was taking care of a child that may have been fathered by a friend of his who was conveniently dead. The Democrats had turned up reports of marital infidelity by Blaine, but they opted not to retaliate with more sex scandals. The 1884 campaign was the last time until the time of Bill Clinton, where marital fidelity became a big issue in a presidential election. Summers believes that the two parties realized that making every campaign about morals issues was bound to be a disaster for both sides.

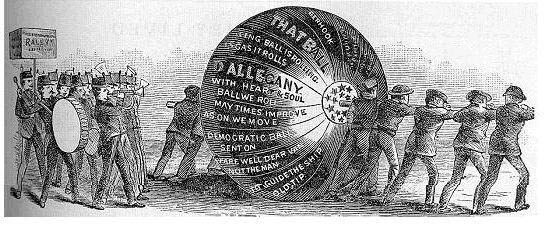

What were the issues of the day? There was the tariff (high tariffs were sought by the Republicans, while the Democrats mostly wanted them lowered), Prohibition (an issue that served mostly as a wedge issue between evangelical Protestants and Catholics), and the Civil War, which was still being fought in the political arena.

The Democrats had a solid base of 153 electoral votes in the South, so Blaine needed to sweep the three swing states in the North: New York, Indiana, and Ohio. Blaine didn’t do it as Cleveland’s narrow win in New York (by a little over 1,000 votes) was enough to tip the election to the Democrats.

One of the crucial moments in the election campaign happened on October 28, 1884 in New York City. In the last days of the campaign, Blaine made an appearance at a meeting of evangelical ministers. The chairman of this meeting was a well-respected minister in his seventies named Dr. Samuel Burchard. Burchard introduced Blaine to the crowd with this address:

We are Republican, and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism, and rebellion. We are loyal to our flag. We are loyal to you.

The reaction to “rum, Romanism, and rebellion” was not positive. Some in the crowd hissed. Reporters present at the meeting recognized it as a huge problem for Blaine because he was now identified with religious bigots. (Burchard claimed not to be anti-Catholic and said he just got caught up in alliteration.)

The news cycle of 1884 moved more slowly than today, and it took three days before Burchard’s words and Blaine’s seemingly tacit approval of them became a national story (the Democrats did have stenographers follow Blaine around waiting for a gaffe). In an election as close as 1884, it didn’t take much to keep just enough Republicans (some of whom were Catholic) away from the polls on Election Day.

Grover Cleveland would end up winning the popular vote in three straight elections, but only the electoral vote twice. He started as President because the country was tired of Republican rule. He left office in 1896 despised by his own party.

Blaine would go on to serve as Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison before succumbing to the same kidney disease (Bright’s disease) that killed his political rival, Chester Arthur. This book definitely makes you feel like 1884 was a very unusual election year. It was. Politics was heading out into an increasingly weirder form in America. And it was never going to get less weird again.